“Your First Lap Doesn’t Count”

By Ben Neiburger (the athlete) and Jack Davidson (his support)

Yes, this race report is long. It’s so long that it is almost indulgent. But for a race so epic as this, the length and detail is completely appropriate. This is also a first-person narrative giving both the athlete’s and his support’s perspectives. Most of the first person is Ben’s narrative, unless it highlights Jack’s sometimes wildly different viewpoint. This is not the story of one of those athletes chasing glory at the front of the pack. It’s the story of survival by a 50+ athlete chasing his personal limits and finding them.

Jack and I wanted this report to contain ample and detailed information that future teams can use to plan their races successfully. So if you get bored, don’t complain, just skip ahead to the exciting parts.

The Norseman is the granddaddy of extreme full distance triathlons. That’s a 2.4-mile (3.9k) swim, 112 mile (180k) bike, and a marathon. But add freezing water, 10,000’ of hard bike climbs in cold weather, and impossible to run runs. In addition, it’s unsupported. That means the race organizers do not provide food and water to the athletes. The athletes must bring someone with them to do these things, and to pick up equipment, and changes in clothes.

The race gives awards only to the top three male and female finishers. If you finish in the top 160 athletes, you get to climb another 3000’ mountain at the end of the course and receive a black t-shirt as your reward. If you are not in the top 160, you get a white t-shirt. There are no age group awards, no prize money, just a t-shirt. The black t-shirt is the most coveted piece of clothing in the triathlon world.

Also, this race is popular. It’s on the bucket list of many serious long course triathletes. Because of the race’s remote location starting in a rainy Norwegian Fjord, there is very little lodging for all the athletes and supports. That limits the race capacity and number of entrants the race permits. Maybe 250 spots per year (typical Ironman races can have 2000 athletes or more). There are additional slots if you qualify by winning another extreme triathlon or are given a slot by a financial sponsor of the race, otherwise you enter the lottery. Many thousands enter the lottery, but very few get in. Some people try for years and years and never get a slot. It’s like Willy Wonka’s golden triathlon ticket. In 2019, I got in on my first try (and deferred for two years due to COVID). I know, hate me now. But, as the Norseman moniker points out, after you read this, you may decide this race is not for you. It almost wasn’t for me.

PART 1 – Getting Gear to Norway By Litigating Murphy’s Law

For the Saturday morning triathlon race, Jack and I started our trip by getting to the airport in Chicago three hours early on a Wednesday to make sure our bikes got into the belly of the plane. This was a major stressor, given all the news about bikes being lost in transit to Europe. The plane took off at 7:30pm on the dreaded overnight “you ain’t sleeping much” flight to Norway via Iceland.

At O’Hare with bike bags in tow

Both Jack and I packed the frame and wheels of our bikes in our two-part Ruster Hen house bike bags. We’ve used those bags to avoid the more expensive airline “bike luggage fee.” I took my triathlon bike for the race and Jack took his gravel bike for some epic gravel riding afterwards.

Jack and I installed Apple Air Tags in our luggage to make sure we could track the bikes, since any delay could ruin the race. We planned our race with very little time cushion. We obsessively watched the icons for our bike bags traveling around the airport to get on the plane.

When we arrived in Iceland six plus hours later, we immediately turned on the Apple Find App to discover that Apple still thought that our bags were 3000 miles away in Chicago. However, as the iPhone connected to the local network (T-Mobile, “Welcome to Iceland, we are happy to offer slow data speeds for free, but if you want to have a voice call, it will cost you $0.25 per minute”), the App comfortably said, “With You”.

Resting at the Iceland airport

After a brief trip through passport control, we had a four-hour layover (We could have chosen a 45-minute layover, but we didn’t want to risk a short connection with the bikes left behind).

One key to having a successful race is to arrive at the starting line uninjured despite Murphy’s Law continuing to work its destructive magic. For example, while sitting in the waiting room in Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, another passenger’s carry-on luggage (be sure to put your heavy extra personal carry-on item on top of your heavy carry-on bag. It helps destabilize the bag and provide additional inertia!) tipped over from across the aisle and crashed into my shin. Luckily, it glanced off my shin with a slight jolt of pain, but no lasting damage. I got an “Ouch! Oh, sorry,” from the owner of the dense objects. To add insult to injury, while stepping onto a bus between the Iceland airport terminal and the airplane on the tarmac, I almost twisted my weak ankle on a dip in the concrete. The starting line can’t come soon enough. Maybe coach Liz was right to suggest that I be wrapped in bubble tape and put into a closet until the flight to Norway. Unfortunately, you must take off the bubble tape to fly. Maybe the closet and bubble tape should have gone with us?

Jack leaving the Bergen Airport

Not too many hours later, on Thursday, Jack, me, the Apple Air Tags, and our bike bags arrived in Bergen, the fjord capital of Norway. The four bike bags came off the conveyor belt in Bergen airport’s cavernous baggage claim area. Looking out the windows, Norway’s West Coast greeted us with clouds and rain and hills as far as our eyes could see. Our second flight was uneventful, having much more legroom than the first. I caught a nice nap on the plane to prepare for our drive to Eidfjord. Since the race starts on the West coast of Norway, goes over a central mountain plain, and descends to the east coast, the start was closer to Bergen and finish closer to Oslo. Rather than have a long drive to the start or the finish, we flew into Bergen and leave from Oslo. I think the drive from Oslo to the start at Eidfjord would have been too much right after 20 hours of travel.

In line for the rental car, we met several other people with bike bags. One of them was the infamous iron cowboy who had done 100 triathlons in 100 days under some sort of controversy. But he was very pleasant and gave us some race advice (he got a black t-shirt in 2015 or 2016). Mostly that w

hen you get to the infamous Zombie Hill on the run (15 miles in), it’s difficult to pass people or to be passed. At that point, he said, your placement is mostly set. You can only walk up that hill. Excellent. I’ll just change my race plan and run as hard as I can for the base of Zombie Hill.

With the Iron Cowboy

We rented a Volkswagen hybrid station wagon and waited for 10 minutes on side of the highway while our GPS software synced with Norway roads so that we could find our way to Eidfjord.

We then started our 2.5 hour, 93 mile journey to the race start. In the fog, the rain, and through more tunnels than I have ever

driven through in my entire life. The scenery was absolutely gorgeous, going through fjords with waterfalls, narrow roads, and lots of oncoming large trucks. I had many visions of head-on collisions if someone (or sleep deprived me) drifted over the centerline, but no one died and there were no close calls. Based on the road and tunnel construction we saw, I think Norwegians like to show off their engineering prowess. “Oh look, there is a Fjord cliff wall that couldn’t possibly hold a road. But we are going to put one there, anyway. Just to show you we can. And, yes, some of them are so challenging that we will just bore out a 3km long tunnel, uphill, and avoid the switchbacks. Because we can. We are Norway.”

After a couple of hours, we stopped at a rest stop to get food and water at a very cute café/gas station with a clothing store attached. While going through the displays at the store, Jack noticed that there were no bathing suits at all like in some US road side stores in the summer, but everything was rain gear. All of it. RAIN. Ominous.

The suspension bridge in the clouds.

The road tunnels turn into some of the largest hollowed out caverns I could imagine with roundabouts. You had to remember what your GPS told you before you went into the long tunnel so you could figure out what direction to go at the roundabout in the center of the mountain tunnel.

The last tunnel roundabout we went through exited onto a beautiful suspension bridge set in the middle of the clouds and a light drizzle. The scenery was unbelievable (Think Jurassic Park for Dinosaurs that like the cold) and, of course, waterfalls. Lots and lots of waterfalls.

Fjord view from the back of the hotel

Hotel Voringfoss

Yes, this is from the swim course.

We arrived in Eidfjord around 7:10 PM, the day still dazzling. Eidfjord has the same latitude as Juneau, Alaska. We checked into the race hotel, Hotel Voringfoss.

PART 2 – Pre-Race Jitters

As we crossed the hotel entrance threshold, tons of skinny, chiseled athletes seemed to surround us. This, being my first world championship race, I had no idea how intimidated I would feel around these superhumans. My confidence in racing well crumbled. I started my self-affirming mantras (all lies!): “Do what your body can do,” “Implement your race, no one else’s” “You are not less of an athlete because you don’t have the body of an elite athlete, LIKE EVERY OTHER PERSON HERE!”

When I tried to check in, I didn’t realize that the reservation was under my wife’s name when she made the reservation for the race in 2020. So, despite many emailed confirmations, it appeared that they had no reservation for Jack and me after almost 23 hours of travel. Then I started, calmly, to throw out names and I realized the reservation was under my wife’s name.

The cruise ship was docked in the home stretch of the swim course.

The rooms were simple and nice. The hotel grounds are beautiful. There was a cruise ship docked on the wharf just outside the hotel, a large “Viking Cruises” ship, aptly named.

Since it was late, we immediately went down to the hotel for the evening buffet for adequate and very good “athlete food” for $45 a head (yikes!).

After dinner, I assembled my bike, bragging to Jack how it would only take me 15 to 20 minutes to put it together. No problem. An hour later, my bike was together, and I took it for a short spin. Jack smiled, saying nothing.

Being very sleep deprived, we were worried about getting a full night’s sleep. After some restless hours in the middle of the night, we slept about 7 hours. Little did we realize the effect of how very little sleep between Wednesday and Saturday would affect my performance and almost cause my race to end early.

Bright and chipper the next morning, we went down to the hotel breakfast for more self-imposed body intimidation. While I can use my grit to accomplish most things that I put my mind to, the one thing I haven’t been able to do is to moderate my food and alcohol to reduce my body fat percentage from 25% down to 15% or less. I think I was the only athlete there with a middle-aged belly. In fact, most of everyone we met thought Jack was the athlete (tall and thin), and I was the support.

Jack:

Ben and I had a rough strategy planned for support over a dinner or two back in Oak Park, Illinois, basically just making up stuff based on what we’d read so far, materials that another athlete, Lani and her mother Betty gave us from her 2015 race (incredibly helpful for our packing lists), what Ben was seeing in the athlete-only Facebook group and the Athlete’s guide. We had our aid stops penciled in on the course and felt we’d alter as needed on race day. As we’re having breakfast the day before the race at the Voringfoss hotel trying to look like we knew what we were doing among the slim, chiseled, sponsor-laden athletes from all over the world, I overheard a woman talking to her team at a table right by us, and she was an American roughly our age. I encouraged Ben to introduce himself, which he reluctantly did as we were finishing up breakfast, and that would prove to be our first pivotal moment of the race. Sami the athlete immediately introduced us to Hans and Elisabeth, two Norwegians who had both completed Norseman themselves and supported other athletes several times. These two were brimming with experience. Sami let us know she was basically untrained for this race because of a recent crash resulting in broken bones and a COVID infection, but was determined because she’d attempted a lottery draw for 9 years and finally got her golden ticket. Sami has some serious long course athlete credentials as an athlete and an ironman race director. She introduced us to her partner, Charlie. It thrilled her to meet Ben and commiserate with him and was looking forward to having a fellow American to partner with for the remaining pre-race routines, including the practice swim and bike shakedown.

After breakfast, I squeezed into my wetsuit to take part in the day before the race morning swim. I really didn’t want to do the swim, but Sami was very enthusiastic that I should jump in the water with her. At the edge of wharf, there were lots of excited athletes people dressed in wetsuits, thermal gear and parkas! The water was 55°F.

The swim area was by a pier jutting off the side of the large wharf (no cruise ship today). As each athlete jumped off the pier, you could hear a cold induced scream. Except for the Norwegians, of course. Several of them didn’t even need wetsuits. Superhumans. Meh.

It’s colder than it looks.

I did the swim with no headgear because I don’t enjoy swimming with anything more than a swim cap on my head and the water wasn’t THAT cold. With trepidation, I went down to the edge of the pier and stepped off. I was wrong. The water was chilly. Freezing. My hands quickly numbed, and my head hurt. For the first couple minutes in the water I thought, “Oh boy, I need to go back and get some warming headgear and booties.” But, after what seemed like five minutes (it was two minutes) everything went numb enough to not have any problem with the temperature of the water. Melt-water feeds the water in the fjord from the mountains. So, it was cold and not salty at all. I swam from 600m to 700m and made a break for the warmth. There was a bit of chop in the water, but it wasn’t too bad. The fjord walls with the green and wispy clouds were majestic and it’s always a fantastic swim when you can see snow on the mountain peaks as you plow through the water.

Following the swim, I went to the race registration in the hotel. There, they had swag you could buy for wonderfully inflated prices. What I remember from my last extreme triathlon is that the stuff you buy at the expo are the things that you remember the later on; so, I got lots of clothing, coffee cups, hats, and things.

The registration process took 10 minutes. Then we went back to the hotel room where Jack was finishing his bike assembly. To prepare for a long gravel race in a couple of weeks, he had a three-hour ride and was quite itchy to get that going. Before then, I dragged him down to registration to listen to 10-minute presentation about certain aspects of the race so he knew at least some detail on how to keep me alive. There we met the race director who gave Jack a safe bike route for his training ride. Instead of heading out on the racecourse (there were tunnels that were open to only automobile traffic), Jack headed on the road back towards Bergen and the bridge in the clouds for a three-hour tour.

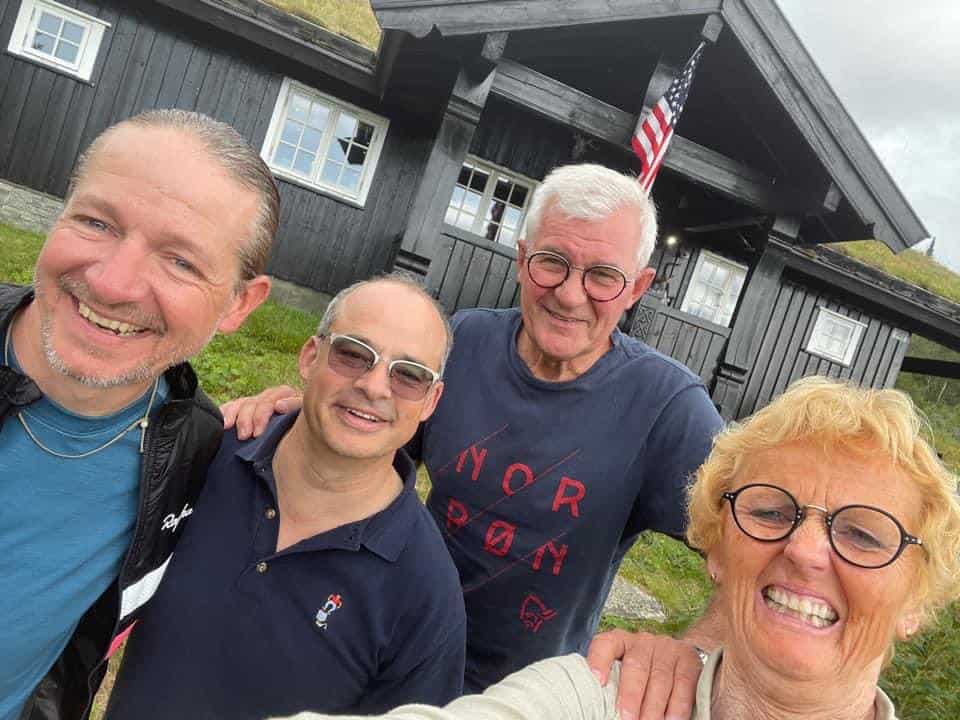

We went to lunch with Sami, Charlie, Hans and Elisabeth. When I learned Hans is the only person in the world who finished an extreme triathlon after a quintuple bypass heart surgery, I knew we were in for a treat and great race mentors.

Jack:

Hans and Elisabeth at their cabin post race.

When I returned, Ben texted me he was having lunch with their crew, and I should head over to join them. After we ate, Hans and Elisabeth began sharing some advice about crew support responsibilities—and that’s when I realized our race plan was trash and we needed to absorb everything humanly possible from these wonderful Norwegians and adjust our strategy based on what we learn.

PART 3 – Race Briefing and Last-Minute Planning

The pre-race briefing was held in a school auditorium. They handed out booties for everyone’s shoes so the gym floor you wouldn’t get dirty.

The meeting started with an eight-minute video on the race that gave no content and a very brief explanation of what will happen on the course. The race director mentioned one section of road that would have a rough gravelly surface during a fast downhill, but no other pavement issues. They warned us the race hired a police officer to follow everybody around to issue moving violations for inappropriate behavior (after the race, the race director said everyone behaved and no moving violations issued). Since there were no Co2 cartridges at the race expo (we use those to fill tires when we flat) (or a bike mechanic) at the race briefing, I got my CO2 cartridges from somebody I met on the Norseman Facebook group who picked them up in Bergen for me. It was like exchanging clandestine goods, secret, from someone you barely know, $5 per cartridge, right under the gym EXIT sign.

At the end of the race briefing, they had “a little edition of culture” in which there were two men, one playing the accordion, another one doing a Norwegian dance in which the dancer occasionally did a flip. I didn’t know how to react to that, but the performers looked thrilled.

After the race briefing, we could ask lots of questions of staff; however, information on the protocol for aid stops on the bike and the run were scant, and that made Jack and I uncomfortable. We barely knew what we were going to do, other than the race plan we cobbled together from the internet.

We went to dinner with Sami, Charlie, Hans and Elisabeth for spaghetti and meatballs. During our dinner conversation, Hans and Elisabeth (sharing their experiences from five Norseman races) became my favorite people on the planet.

Jack:

During dinner, we pulled out our race plan paperwork, pens, and began making changes. Hans knew what the weather was going to be like at T1 and then at Dyranut, where Ben would have just completed climbing 4,300 feet in just 23 miles from his T1 departure. The news was not good. As a result, Hans and Elisabeth recommended support stops from the lens of what Ben would experience at those exact moments. Our attempt at sketching out a strategy over dinner at home was primarily based on when Ben would need refueling, but we didn’t consider what he’d be feeling by those stops, and this was pivotal information that led to a significant change in strategy.

According to Hans and Elisabeth, support should follow behind the athlete and occasionally leapfrog in front of his position to distribute aid. That way, the support would always be there in case of problems, drastic changes in weather, and every so often wellness checks. This differs greatly from what we initially thought, which was going forward several hours and wait for the racer to catch up. Given the conditions the next day, this advice kept me out of an ambulance, or worse. This model was much different than last extreme triathlon, Patagonman, in which my wife rode on a bus from designated checkpoint to checkpoint with food and clothing changes. That strategy would have been fatal for this race.

Our revised race and support plan started by keeping in mind that the race day weather forecast was 50F and rain. I planned to dress lightly and just for rain at the beginning of the climb, but by the finish of the climb, I needed to dress warmly. My body would quickly cool after the hard effort. Hans and Elisabeth suggested good places to stop the car and how to do the leapfrogging. They assured us there were only two turns on the bike course that are almost impossible to miss (well, Jack missed the second turn but found his way back within plenty of time to keep me alive). After T2, the support leapfrogs the athlete and periodically checks in with and encourages the runner for the first 25k of the 42k marathon. After that point, the support drives to the hotel at the end of the run course (where we were staying the night), checks in, and gets everything ready for the finish. Hans said he would watch the athletes and would let Jack know if I could make the black shirt cut off or not. This way, Jack would know which supplies to bring to me after check-in. Jack planned to meet me by walking from the end of the racecourse down Zombie Hill. If we made the black T-shirt which was the first 160 racers, then we have to have mountain packs because the top of Gaustatoppen mountain can be freezing. If I did not make the cutoff, then I would run the “white” course to the hotel. Ominously, to finish the full marathon distance, there was a 600m circular course at the hotel that the athletes would circle 10 times. I gave Jack the option of not running those 10 laps with me since they sounded mind-numbing. [insert ominous foreshadowing music]

The night before, the race was very restless. We tried to go to bed around 9:30 PM to catch four hours of sleep. We slept restlessly. We must’ve had an hour of sleep. Jack added up all the sleep we had since we left the United States, not counting sleep on the plane and occasional naps while traveling, and we got seven hours of quality sleep in the prior three days to the race. That would certainly affect our race day.

PART 4 – Race Morning

We got up at 2 AM. Breakfast conversation revolved around last minute mental preparations and racking the bike in the transition area on time. Finishing our breakfast and coffee around 2:45am, we ventured out into the cold rain to set up the bike. The temperature was probably between 45 and 50F°. I was really worried about how that rainy bike would feel after a cold swim.

I ate two large bowls of oatmeal thinking about the calories my body would require during the day. Usually, I only have one bowl, but I thought this could be a very long day (never try something new on race day). I thought there would be enough time to digest the extra food (two hours between breakfast and the swim’s start). So I took that risk and it made me nervous for a couple hours. Morning digestion seemed to go very slowly.

I was also worried about sitting in an open ferry. For the Patagonman race, the ferry was a cold open platform with no inside lounge. There were visions in my head of me freezing on the metal car deck and then jumping into the freezing water for warmth. Sometimes your worst fears don’t come true.

Jack:

My day started off predictably at 2am Eidfjord time, but Ben’s watch beeping from some unknown & unsilenced notification interrupting both of our sleep time had me wide awake well before 2am (It was an Uber notification to sign up for something stupid accompanied by a chime). We waddled down to breakfast very sleep-deprived but had plenty of time to eat and ease into the reality that it was a race morning for Norseman with a 4:00am ferry departure. Ben sat with his back to the window facing the swim start and the fjord’s icy waters as confident as ever, but I couldn’t pry my eyes from just how terrifyingly dark outside and black the water was. Oh, and of course there was a steady, unrelenting rain. We finished up breakfast, made what seemed like a half-dozen trips back to our room to finish preparations, and then spotted Sami and her team in the lobby. Ready to race now, we all went out to the dock where the ferry was waiting, Ben and Sami posed for a quick photo, and off they went—and back into the warm hotel Charlie, Hans, Elisabeth and I went . . . to drink more coffee and wait for our swimmers to return. As we relaxed for the last time for the next 20 hours, casually sipping more coffee and conversing about multi-sport and the race. Hans and Charlie shared more information with me to help put Ben in the best possible position to succeed. At that moment I realized our “team” had expanded—it wasn’t just Ben and I, now we were a two-athlete team, and it would stay that way through to the finish.

The rainy start on a cold morning.

Ben and Sami getting on the Ferry

The ferry was an electric ferry. Love the Norwegians! It had ample indoor warm accommodations, comfortable tables and lounge chairs.

Part 5 – The Swim

I sat at a comfy warm table with a friend of mine, Lars from Aruba (he and I did Patagonman together), Carlee, who I had met the day before, and Sami.

We had a delightful conversation until the powers that be behind boomed instructions from the loudspeaker that it was time for everybody to jump off the ferry. As I looked out the dark window, I saw what I thought was an incredible rainstorm pelting the ferry windows. I felt dread towards how I thought this would work out after the swim.

As we exited the second floor of the ferry’s lounge to go down to the ferry’s stern to jump, I saw the rainstorm was really a hose some sadist was using to hose down each athlete before the swim. The theory is to have your body warm up the hose water before you jump in so you would have less of a shock when you jump in. Bullshit. I ran through that water stream as fast as possible so not to get wet and cold any earlier than I had to. We then jumped off the ferry and had to swim a 150m to the start marked in the twilight with a line of kayaks. Oh, the fjord is rumored to be 1300’ deep.

The jump!

Not too much chop in the 57 degree water.

The swim followed the fjord coastline back to town, a 3800 m swim. The advantage of jumping off the ferry and then waiting for the start line is you make sure that your goggles are on and don’t leak. Oh, and that you get used to the COLD water. The water was 57F. The first minute to a minute and a half in the water was freezing and uncomfortable. It was not a merry time. Then uncovered body parts went numb, and all seemed good with the world.

The crowd in the water was very excited. We treaded behind the starting line kayaks while swimmers still jumping off the ferry swam to us to gather near the start line. After 10 or 15 minutes, the ferry horn went off. Because of the quality of the athletes, the mass swim start was crowded and aggressive. In the middle of the fast-moving bodies and the jostling of people drafting off each other, the sun had just come up. The sun’s heat created mist along the sides of the fjord. The heat dissolved some of clouds revealing SNOW at the top of the mountain peaks. After a while, the sun went away, leaving a wispy rainy, cloudy ominous looking haze. The fjord is quite beautiful with lots of trees. Above the swim course was the road from Bergen to Eidfjord. On the road, tailgaters beeped their horns and made lots of noise to cheer on all the numbed-up swimmers.

Swim Course (this view does not include the snow on the peaks)

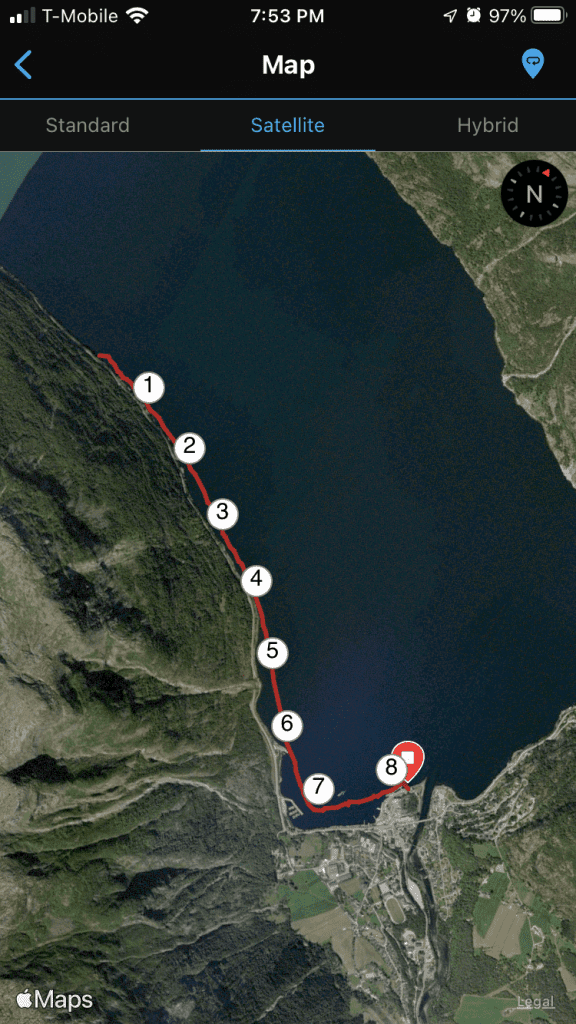

The swim course followed the coast for 3200m and turned left turn around a large yellow buoy. The swim exited past the wharf. At the turn, the water temp dipped from 57F to 55F. The swim was uneventful. I tried to hang on to the feet of some of the faster swimmers, but they kept dropping me like a bad date. My swim pace was slow for me, 1:55 per 100 yards. I don’t understand how it was so slow. However, it helps your swim time if you sight objects on the shore correctly so you go in a straight line and swim less distance. There was a light on shore just past the buoy that many sighted on. There were swimmers who followed too close to the shore, swimming more than they needed to. In fact, some of the faster swimmers who went wide while hugging the shore caught back up to me near the swim exit. There was a current too. The farther away from shore you were, the stronger the current. I learned later, there were some slower swimmers who caught a reverse current and swam almost 5000m in the water for 2.5 hours, past the swim time cutoff and not able to finish the race. The sighting set up was an example of why you need to look at the course before you do the race (I know it’s a basic thing, but I could only scout the swim course in advance. That hurt my bike and some of the run – another disadvantage of arriving at the race too close to the start—however, I don’t think it made much of a difference).

As we finished the swim, people in winter coats on the wharf hooted and hollered encouraging noises at the athletes.

Near the end of the swim, my calves cramped. The cramps were quite painful, and I had to flex my ankles to decrease the pain level as I swam. I finished the swim in place 95 out of 239.

Swim Exit

The swim exit was this small ugly patch of coarse sand hosting lots of angry large pebbles. The sand ended at a small grassy hill. And then there was the rain.

Jack:

Suddenly, I noticed lots of race crews clamoring around the windows of the hotel as daylight broke, and I squinted to notice the lead swimmers were nearly back already! Dammit, I had lost track of time! I scrambled outside where it was still raining, and I really did not know what to do next. We had set up Ben’s station in T1 with his bike and gear before breakfast, so that wasn’t the issue, but now there were what seemed like hundreds of people crammed together along the shoreline near the swim exit, and I panicked. I didn’t rehearse what to do next including where to stand and how I’d spot Ben coming out of the water, much less how I would enter T1 to assist with getting him on his bike. I anxiously texted Charlie, asking him where the entrance to T1 for support was, but I didn’t hear before the first swimmers began exiting the water and running through. My HR must have been in zone 3 while standing still at this moment. I stood on my toes and watched each swimmer exit the water, hoping to get a glimpse of Ben. I then remembered that his time goal was around 1:15, so I relaxed a little and clapped for the other athletes, peering at my watch every 30 seconds. 1:15 arrived, then 1:17, then 1:18, and BOOM, here comes Ben. I shove my way past the other support people waiting for their swimmers, and he was happy to see me as we jogged through the chute to his bike. His transition was quick but he was already noting that it was too long as we made our way toward T1 exit. Off Ben goes, but then comes my anxiety like a wave. What do I do now? Where do I go? SHIT! Wait, calm down, we have lots of time. Deep breath. Pull up your notes—ah, that’s right. I need to get all his gear together, check out of the hotel, get my bike up on the roof of the car… pack the rest of our stuff in the car, plenty to do. So I go through these tasks, start the car, and look around. More panic—It’s pouring rain, and I don’t even know what direction to turn coming out of the hotel parking lot! Relax, more deep breaths, I spot another support car departing the hotel, and quickly begin following them out on the course.

After running left at the top of the hill, I found Jack standing nervously by my racked bike ad gear. The race officials required your gear to be in a wooden box next to the bike. There was no setting out the gear in advance. Plus, it was raining, and you wanted to keep your stuff dry (ha!). It was a light rain that didn’t seem that bad. Jack helped me get my bike clothes ready as I stripped the wetsuit. Based on our planning sessions, I would wear regular bike shorts, a jersey, bike raincoat, hydration pack, and shoes and socks. The only waterproof thing I had was my cycling rain jacket. The transition was slow, 10 minutes, especially because they would let me out of transition without the reflective vest on the outside of my rain jacket. So, I had to take off the hydrations pack, rain jacket, reflective vest and then get it all back on again in the correct order.

The first 8K of the bike was relatively flat and rainy. I thought the cycling rain jacket was working well, and I was comfortable. Normally what happens to me on the bike is that as most the field passes me, yelling “Nice Swim!” as they go by. No one said that today. They just passed me like elite athlete freight trains. I’m not that strong of a cyclist, and I weigh more than I should, so it was enough just trying to keep my pedaling efforts at a reasonable level while using my

Out of the water and still wet.

new 34 tooth chain ring to climb slow and steady. Before the race, the excellent gentlemen at BikeFix removed the rear wheel 11-28 cassette (11 teeth on the smallest ring and 28 teeth on the largest-the more teeth the better climbing power you have, but the slower you go) and replaced it with an 11-34 cassette. The 34 tooth chain ring saved the race for me as I couldn’t have done this climb on a 28. I didn’t have enough horsepower for that.

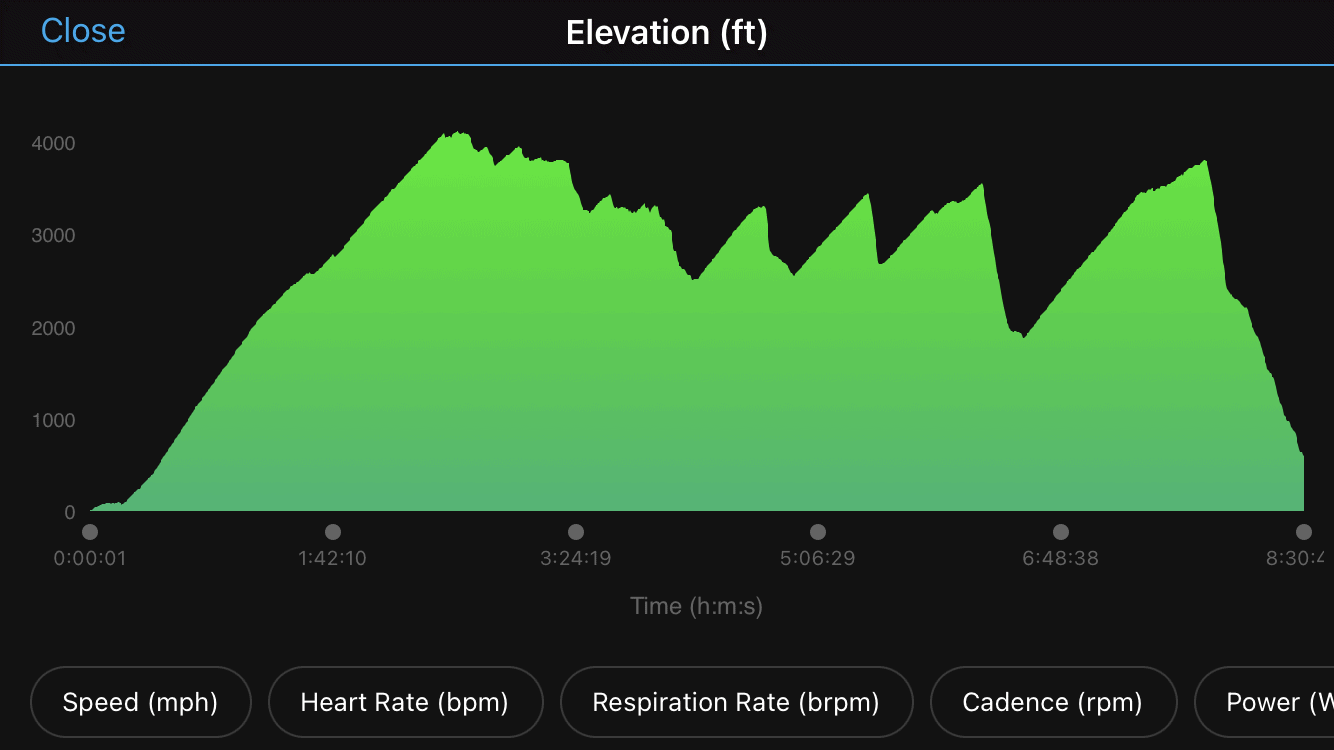

PART 6 – The Bike

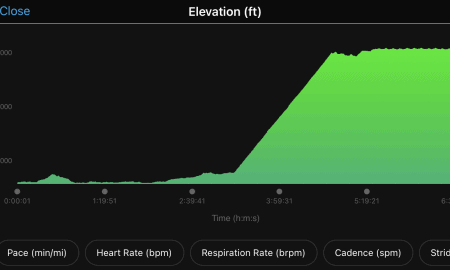

Starting at 8 km, the climb began—4000 feet of it (sorry to mix standard and metric, but I really suffered on this climb and measuring it in feet rather than meters makes me feel more accomplished) until the top at 36 km near Dyranut. During the climb, I tried to think what was more amazing, being able to bike Lower Wacker Drive during the Chicago Triathlon, or biking through Nordic tunnels cascading with rain. If the movie Batman didn’t film on Lower Wacker, the Norwegian Tunnels would have been cooler. But with Lower Wacker, you know it’s going to end soon. It doesn’t go on forever, upwards. We biked through several automobile tunnels, one over 2 km long. This segment of the bike course had an average grade of 6% but there were some sections that were up to 18%. I got through those without crying. There’s a 3% average grade with an 8% maximum grade over 832 feet from 16 to 25 km. It’s a 4.4% average grade with an 8.2% maximum grade for a climb of 1300 feet from 25K to 36K.

I was really happy someone put a tunnel here.

Non. Stop. Climbing. in. the. Rain.

The climb was wet. Because the race starts on the Western side of Norway, climbs up the mountain range, crosses a central plateau and descends the eastern side of the range, the race director told me that you will get all the weather systems. It just depends on what area of the course you are in and how it hits you.

I had no idea what to expect when I got to the top of the hill and this plateau. Hans and Elisabeth told me that it would be cold, and I would need to change into warmer and dry clothes. Jack and I decided that our first stop would be at a town called Garin which was at 20K. When I got there, the weather was wet and tolerable. I told Jack that this was the hardest climb I had ever done and that I thought we could do a clothing change at our next support stop around the town of Dyranut at 36k.

Jack:

Ben’s first support stop goes according to plan. He’s wet but doing okay because he’s mostly climbing and maintaining a decent core temp. I capture him on a quick video as he pulls up saying “that was really hard! Shit!” but he’s in great spirits. A quick bottle swap and top off of his nutrition, and he’s away again to continue climbing.

Even the best-laid plans sometimes go wrong, and what would appear on the surface as a minor alteration, not being a big deal, quickly devolved into a critical mistake. As Ben approached the top of his initial long climb, I remembered our revised strategy of stopping just before Dyranut for two reasons. The first reason I remembered, to avoid the cluster of all the rest of the support cars, all stopped in the same spot, and I couldn’t (for now) remember the second reason—I’m sure it will come to me.

The rest of the bike from 21 km to 36km was a cold foggy slog with lots of athletes passing me. To miss the crowded aid station, Jack would meet me a couple of kilometers after town. It sounded like a great idea. We texted with each other to coordinate but my contact lenses created a problem. I can only see far away in them. Everything nearby, including the text messages on my bike computer and texts on my phone, is blurry. I wore contacts so that the rain did not cloud my glasses and make me completely blind.

As we got over the top of the mountain and went towards Dyrnaut, I swear it snowed. Fog completely covered the road. It was wet; it was cold, and the wind was blowing. I became hypothermic as my body quickly cooled. The air temperature was in the mid-30s F and the windchill was in the mid-20s. Later, we would learn that this was the coldest temperature ever recorded at Norseman. At the time, I felt I would turn into a popsicle. Mid-freeze Jack texted me he was a couple kilometers from where I was.

Jack:

As I pulled up to the designated support area, I realized I drove too far and now was in a parking lot with tons of waiting support cars. Ben hadn’t physically laid eyes on our support car yet with the bike on top and in full-race-support mode, and my parking location within that lot was a bad spot for Ben to sight me, so I made the executive decision to drive further down the road to find a more ideal spot for this crucial stop where we’d remove Ben’s wet/warm kit and get him into his wet/cold kit with lots of layers for warmth. I stopped further up the course about 3k or so from the designated support area – happy with my choice, and I wait for Ben to arrive. I notice the wind is absolutely howling, but I have been in a warm car with a blazing-hot seat warmer for hours now, so I was oblivious to just how much the conditions had worsened since T1, and how much colder it was up this high. Here he comes now. I’m excited to see him, but as he rolls up, I can tell he’s suffering significantly.

25F with the windchill. Going hypothermic and beginning my uncontrollable shivers.

I finally found Jack and pulled over, shivering uncontrollably. I asked him to move the back of the car around so I could change out of the wind. So Cold. We stripped off most of my soaked clothes and got out the warm bike clothes bag from the race supplies. I just couldn’t stop shaking.

Jack:

Ben asks me to reorient the car so he can hide behind it as much as possible to block the gale force wind, and I meet him at the tailgate and start tending to his bike and restocking his nutrition. With that task complete, I move over to Ben and notice every limb on his body is shaking uncontrollably, and he’s soaked from head to toe. I help him remove his socks, and his feet were as white as this page. I think to myself—oh shit—not realizing my mistake put him in this hole, but I think something I would repeat to myself many, many times throughout the day “there’s just no way!”. Ben is so cold he’s removed nearly everything from his body, and still wet, he puts on dry clothes still shaking uncontrollably. His spirits somehow remain positive. I give him some moral support and remind him that his core temp should rise now that he’s in better technical gear for the plateau section of the ride.

Much warmer now. Sort of.

We found all the warm clothes that I had; we changed my socks (although my shoes were still wet – I think in the future I need some neoprene bike socks and some waterproof shoe covers), and tried to get me in as warm clothing as possible including a technical base layer, vest, arm and leg warmers, balaclava over my head, and thicker gloves. My cycling gloves were completely wet. That took about 15 minutes before I could go forward again. It quite demoralized me at that point, but I knew warmer weather was ahead, allegedly.

Jack:

As we’re getting ready to shove him off, I notice something rattling on the front end of his bike. I lift it up by the handlebars, and the front wheel comes off! The wheel quick release is open, and his wheel was loose that entire stretch! OMG! Wheel fixed, the rest of the bike checked out, and off he goes again.

It’s bad riding in the cold weather cold. I powered my bike across the plateau to seek warmth from both inside and outside. To my further horror, after 2 km of frigid pedalling, I noticed I didn’t fasten my bike helmet. The road was windy, with no shoulder, foggy and wet. I had to decide whether my life would last longer by getting out of the cold quicker or having a fastened helmet if there was a fall. I was still shivering uncontrollably. I stopped the bike to fasten the helmet, but I couldn’t feel the buckle through the gloves. I didn’t want to take off the gloves because I could no longer feel my fingers. Decision made, the gloves came off, fingers froze, helmet clipped, and I was off again.

Jack:

A desolate and windy plateau.

I sat still for a few minutes, reeling in all the drama that had just occurred—DURING OUR SECOND SUPPORT STOP—and I remember the 2nd reason for the revised stop strategy from Hans and Elisabeth. When Ben stops climbing, his core temp will IMMEDIATELY drop because of the horrible weather at Dyraunt. My decision to stop a few kilometers BEYOND the support stop might have put Ben in an unrecoverable hole. He now has ~37 miles of flat to ride and hopefully warm back up.

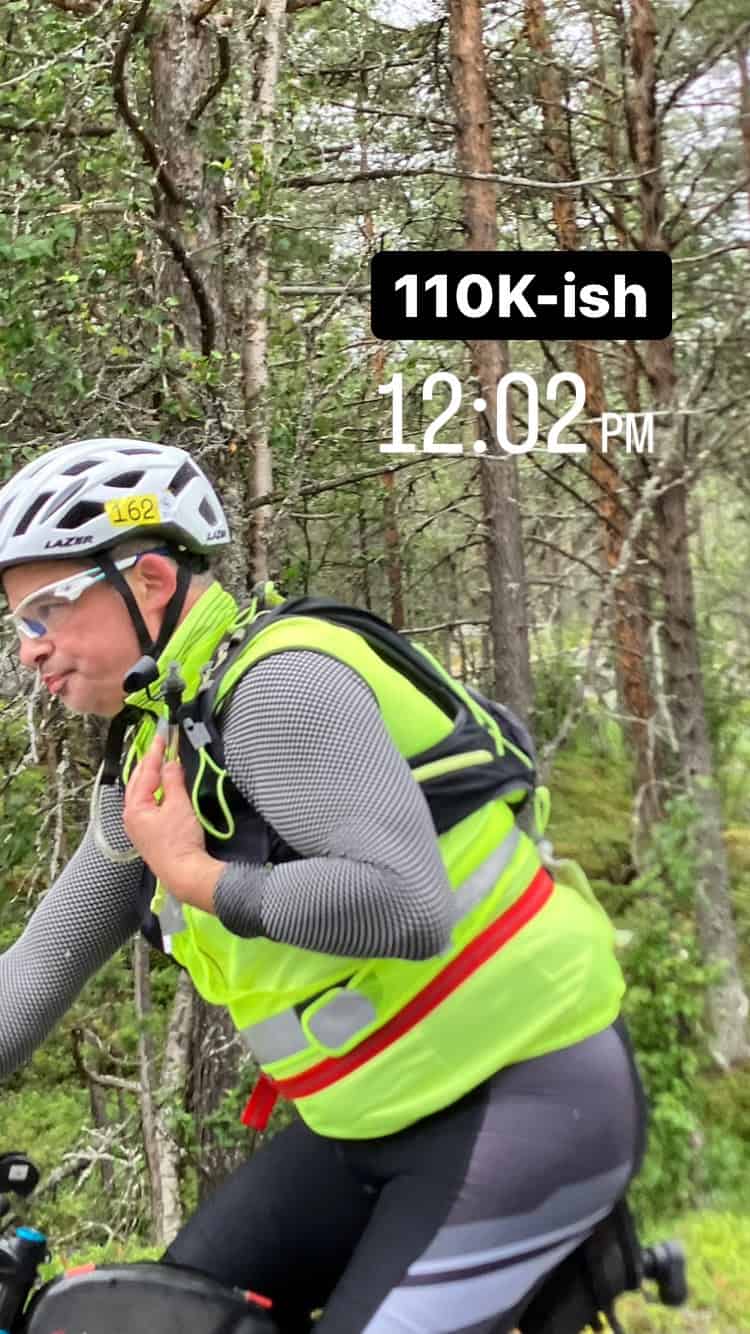

As I travelled across the windy plateau, my nutrition plan fell apart. While I had practiced eating my non-sports food during training, I had not practiced consuming my nutrition while wearing winter cycling gloves and a balaclava while shivering uncontrollably. Being always the rebel, other than Gatorade Endurance, I try to use “real food” and not that fancy expensive sports food. For this race, I proudly mixed Toast Chee Peanut Butter Crackers and Pop Tarts. You would be amazed at the amount of processed sugar there is in a Pop Tart. Unfortunately, my nutrition plan was not bomb proof. Since the gloves were so thick, I couldn’t pick up the nutrition without the processed food blowing away onto the wet pavement. In addition, I didn’t want to take off the gloves because my fingers were frozen and I couldn’t get the larger gloves off and on while riding. I didn’t want to stop to take off the gloves to get the food because the sooner I was off the plateau, the warmer I would become and the less I would shiver. I tried to increase calories from Gatorade to compensate, but an hour or two later, I was peeing at every rest stop, which became more and more frequent as my fatigue increased. By the time I got to the next rest stop, I must have spent so much energy dealing with the cold and the clothing that I got a case of “the mumbles” – something that alarmed Jack tremendously. After all, in our five years of friendship, he never heard me (the articulate lawyer) slur my words or create a new language on the fly. Jack gave me Gatorade bottle refills, new Pop Tarts and some crackers. The winter gloves came off.

This town, Geilo, was the halfway point of the bike. Little did we both know that our lack of sleep and compressed travel schedule would haunt our race with a vengeance. By this time, most of the athletes had passed me and I sat in place 211.

From that point, the bike course undulated up and down with some wicked descents over many switchbacks. To avoid panic breaking near each of the hairpin turns, I rode and tapped my breaks hoping the constant pressure wouldn’t wear away the pads. At 106 km there was a pretty big hill and then a 770-foot multiple switchback descent. We stopped for aid more frequently (about every 10k) since I was so shaky. During this time, I had to pee at each rest stop (thank you, Gatorade nutrition), but what could I have done with the glove fiasco to get more calories in? So out the liquid went at each stop. After the race, I asked the guy who came in third at the race, Allen Hovda (who I “raced” at Patagonman—he came in top three, and I was near the back of the field) what he does and he says he sips a gel for his nutrition (of course he doesn’t stop). At that point, I decided, starting the next day, I would never eat peanut butter crackers or Pop Tarts again. Highly engineered sports food, bring it on!

Climbing again, but much warmer.

The lowest point of the race (and athletic career) occurred as I continued to fatigue. I almost fell asleep on the bike during the 1600-foot descent between kilometer 127 and 134. My bike speed got up to about 32 or 33 mph, but at the end of each downhill segment there was a hairpin turn and I was worried about my bike being able to stop for that. I was pumping the brakes the whole time. I couldn’t keep my eyes open. I nodded off during one of these down hills and it terrified me. I could crash the bike and die at these speeds, and I couldn’t stay awake! What would the remaining 46k be like? Constant risk of hurting myself because I didn’t have the foresight to get to the race several days earlier and get adequate sleep? At that point, for the first time in my life, I tried to quit something. It was too dangerous, this was too hard, there was an 11k climb ahead, and then a fucking marathon. No way. So, when I got down that hill an anxious Jack met me at the stop. I told him I didn’t want to continue with the race. It was not safe to go on. My grit had found its safety limit.

Jack:

I waited for him to arrive, jumping out of the car to snap some pics, and feeling the warmer conditions, I was happy to greet Ben with some cheerfulness that the worst of the difficult weather seemed to be over—despite the big climb looming just ahead. As Ben rolled up, I began a short video of his approach and captured him, saying that he almost fell asleep on the descent, followed by “I don’t know if I can continue” and other mumblings of despair. I put away my phone, noticed he had yellow cheese cracker smudges all around his mouth, and thought I heard him slurring his speech, which to me was odd at this point because the weather had improved at our current elevation. We discussed a short-term plan to address his fear of imminent death from crashing if he falls asleep again with some potato chips and a half bottle of coke. We then decide to take the climb in tiny chunks and make progress a couple of meters at a time. As I get set to pull on up ahead, he says something to me that sounded like he mashed three words together inadvertently, which triggered more concern from me on his overall condition.

By this point, and before he saw me at the end of the descent, Jack was anxious about my ability to continue. He hadn’t seen an athlete in a race presenting as poorly as he thought I was. I think he texted with my coach, Liz, and his coach, Amanda, and the other athlete from our athlete group who had finished this race in 2016, Lani. They all encouraged him so he could get me going again and not quit. The savior of the race was a bottle of Coca-Cola that I got the day before based on a conversation with the Sami. She offhandedly told me that there’s nothing better in the middle of the racecourse than a can of Coke. The caffeine in the Coca-Cola woke me up quickly, and I lost my fear of falling asleep while bombing a hill. Even with the caffeine recovery, I still didn’t want to go up this hill because it was a 7% grade with a 9% maximum grade up 1500 feet over 11 km. I just did not want to do this bike. They say in the advertisements for Norseman, that no one can finish this race alone; so true. To get me to continue, Jack said we would do the hill in segments. He crept the car ahead of me and had it within sight of my bike as I slowly ascended this last monster.

Previously, all the cycling climbing I have done has been short hills (except for the other extreme triathlon I completed, a 60-mile hill at a grade that is not insane). They were short punchy hills. You go up a couple hundred feet and then you’re done. No biking in the mountains. I think if I would have driven the racecourse, I wouldn’t have started the race. These hills were kilometers and kilometers long of constant climbing up what seemed like endless switchbacks. It was tedious and hard. But I knew when I got to the top of this (at Imingfjell) that there was a flat plateau for 10 km and then for the final 25 km of the bike course there was a 3100 feet descent at a -3.2% grade.

Jack:

I keep Ben in my rear-view and drive just slightly faster than him as he starts up a 1500’ climb to the top at Imingfjell. I check in with him repeatedly as we had plenty of opportunity to communicate going up this mountain. He churns away behind me, and I feel like staying close to him at this point is helping him stay alert and make incremental progress. We slowly pass the race markers one at a time, and with each one passed I am getting more excited that the end of this climb is near, and a huge downhill ’ll reward him to T2. Finally, as we zigzag up one more switchback—there are the beach flags signaling the top at Imingfjell, and the 150K marker! He made it! I remember an important piece of advice Elisabeth shared—when you reach the top at Imingfjell, hit the gas and drive quickly to T2 so you are there ahead of him, and off I went. Ben survived the bike leg!

After I topped the hill (and peed again) I found I had the energy again to finish the race. I finished the rest of the Coke and pressed on. The plateau was very windy. I worried about the wind knocking me off my bike so I had to watch my speed and keep out of aero position so I would have more bike control. The plateau was monotonous, and I was exhausted but not falling asleep. Then the climbing on the course ended. There is nothing as exciting as a downhill for 25 km. The first part of that contained some serious switchbacks with a lot of speed. I constantly pumped the brakes, but the speed of the bike held between 24mph and 37 mph. 25k of not pedaling. Well, I would have pedaled if I didn’t develop saddle sores after 9 hours. I even had extra saddle cream on me and just forgot to use it. It was a glorious fast coast.

After I topped the hill (and peed again) I found I had the energy again to finish the race. I finished the rest of the Coke and pressed on. The plateau was very windy. I worried about the wind knocking me off my bike so I had to watch my speed and keep out of aero position so I would have more bike control. The plateau was monotonous, and I was exhausted but not falling asleep. Then the climbing on the course ended. There is nothing as exciting as a downhill for 25 km. The first part of that contained some serious switchbacks with a lot of speed. I constantly pumped the brakes, but the speed of the bike held between 24mph and 37 mph. 25k of not pedaling. Well, I would have pedaled if I didn’t develop saddle sores after 9 hours. I even had extra saddle cream on me and just forgot to use it. It was a glorious fast coast.

Jack:

Transition 2 and the Porta Potty! Only sunny spot on the race course!

I barely beat Ben to T2 having had to park the car in the 2nd, further away lot as instructed by race officials. I had about 2 minutes to look around after setting up his transition before he comes rolling up—phew, that was close! Ben gets off his bike and limps around T2 trying to shake life back into his legs while I get his run clothes ready. We get him dressed for the run, but I notice he’s slurring his speech even more now, but still with good spirits—and an immense relief that the damn bike is done.

Bike elevation profile

I got into the second transition and Jack had just arrived there. The race officials said that I was in placeholder 220 (out of 239). The first 160 get the black T-shirt. I guess that’s just another level of athlete that I don’t think I will ever be. I could do that if I lost 20+ pounds and trained 20 to 30 hours a week, but I don’t think I would want to give up my whole life to chase a black t-shirt (it’s irrationally tempting).

PART 7 – The Run

I spent some time in transition because that’s the first time in the race I could use a porta potty. A highlight of my race plan execution was that I did a great job managing my food the days and nights before the race, so I didn’t have any digestive issues or had to go on the course other than urinating. I also changed into running shorts and used a bunch of saddle cream for all the body parts experiencing excess friction after 10 ½ hours of movement (or with 90 minutes total stopping during the bike, yikes, non-movement – but, I think the bike became an exercise in survival, not time.)

The concept of a marathon after this bike was horrible. I spent some extra time in transition getting my stuff together with Jack helping me. When I started the run, the race volunteers looked at me and thought that I would do a walking marathon. I then flash back to some of the long weekend training sessions Coach Liz made me do. An hour run after a 6:30 hour bike. Endless hiking at the Morton Arboretum. Walk/Run protocols. So, remembering the training, I applied grit and put my left foot in front of my right and started to move.

Jack:

I hustle with him to the timing strip and the race official displays a number with his position relative to the rest of the field. Ben walks away onto the run course while still adjusting things and another race official chats with me, saying “these athletes are the real champions of the race”, noting that Ben will probably have a long marathon walk, but he turns to look at Ben again—and he’s running! That surprised the official based on Ben’s overall condition that we all noticed and commends him for his grit. I personally think Ben will run just far enough out of sight and begin walking again, maybe even passing out and dying on the side of the road before I can catch back up to him in the car. I finally got his bike broken down and everything loaded up, and started chasing him down. When I reach him, I am surprised how far he has progressed already.

Starting the run in the back of the pack, but still moving forward.

The other challenge was that I was so far in the back of the race that I couldn’t see other athletes and the racecourse wasn’t marked well. The volunteer at the run start just told me to follow a specific road, and that was that. I was deeply afraid of becoming lost, or worst, running an extra couple of miles down the wrong road.

So with the fatigue and the fear, I started the run feeling somewhat like death warmed over. I started with a one-minute walk and a nine-minute run protocol. During the run part, I tried to pace at 10 minutes per mile and I ended up being pretty consistent from mile one through mile 10 with maybe a 12 minute per mile average pace, including the walking. At this point, I just kept on consuming my nutrition according to plan (actual sports food—GU Roctane and salt tabs) and never stopped moving forward. As time went on, my pace slowed, the run intervals shortened, and walk intervals lengthened.

Jack:

He’s well set for a while now with two liters of water and plenty of gels, so he encourages me to take off to the finish and check into the hotel and get us tickets for the buffet after the finish. So, I begin the 40-minute drive around the course, and it’s not long before I come up on most of the field just ahead. I pass by dozens and dozens of runners and support cars, eventually reaching Zombie Hill. Up to this point, I know the least about the run course overall and know nothing about this famous hill. The run course is relatively flat-ish up to the start of the hill, which is marked by dedicated beach flags, an ambulance, and a bunch of race excitement with music playing and volunteers all around to stoke the runners for the final big climb. As I turn onto Zombie and start the ascent, the rental car downshifts to the lowest gear and the engine whines, going up.

At mile 10, my legs refused to propel me in a constant run, so I walked more than I ran. I texted people during the walk to keep my spirits up. Unfortunately, the battery on my phone was almost dead. We had a battery pack in the car, and Jack charged my phone during a longish interval until the phone hit 40% battery. During my run we decided he should go to the hotel at the end of the racecourse, to get everything set for the finish. He left me with two hours of water. He wasn’t keen on leaving me, but I told him I would be okay and would text him when I was within 30 minutes of running out of water. I don’t think he believed I would be okay. He came back to give me a water refill around mile 11. Unfortunately for Jack’s nerves, at that point, I might have been slightly delirious. I think I was slurring my speech again. However, I could propel myself forward and convinced him I was “fine.” There was no danger of me stumbling into traffic on the run since I was at the back of the race, alone, running against traffic, during rush hour, with no shoulder, and had my reflective vest on!

What do you mean there’s another switchback ahead? Haven’t we done enough of them already?!?

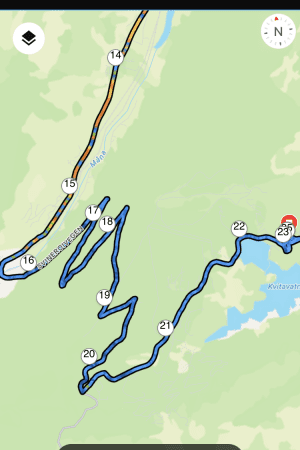

The course still wasn’t marked well although I saw the race Kilometer markers zip tied to various road objects. Not every kilometer was marked. I asked people along the way road if I was going the right direction. My spouse and other friends texted me to see if I was okay, and I even asked one to log into the Norseman tracker to confirm that I was going in the right direction. The biggest problem with all this communication was that I had my contacts in and I couldn’t read the texts clearly. The internet GPS trackers that they had on the course were not very accurate. I think my tracking dot stopped for an hour at some point, making my family fear that I was dead on the side of the road. I kept my forward momentum going. I would see a sign, or a tree, or a bush in the near distance and I would try to run to it. I knew that at kilometer 25 Zombie Hill would begin. Even though I knew it was a 3000-foot climb, it really didn’t sink in what a 3000-foot run climb was (black t-shirt finishers get to go up 6000 feet). Jack talked about the hill at one of our rest stops as very exciting and a huge deal. He wanted to park the car at the bottom and then walk up with me and then get a ride back down to the parking lot. I told him this was unwise since it felt like we’d be out all night, and that he should go to park at the top at the resort and then run down. What I didn’t know is that he would have a 4-mile run descending 2000 feet to meet me to turn around to go up. That would probably trash his quadriceps for his 50k race in several weeks. Jack ended up doing a half marathon of walk run climbing with me.

Zombie Hill has six switchbacks. Each switchback is about a kilometer long. I didn’t know the count when I started the climb.

Yay! Jack caught up to Ben

Jack:

The first switchbacks are very long and a steady 9 to 10% grade up. At this point I am overcome by emotion again, emphatically thinking “THERE’S JUST NO WAY!!!” Ben could make it up this climb in his condition, and as Ben’s support person, I instinctively tried to solve this for him, somehow. So, I picked up my phone, forgetting I am in Norway and called Charlie. He answers his phone and we’re quickly disconnected because of a poor signal because we’re both on US phones calling each other in Norway. Hans is sitting next to Charlie in their support vehicle for Sami, who is slightly behind Ben, so Hans called me back on my phone since he has a local Norwegian cell carrier. I ask Hans in a panic. “There’s no way Ben can make it up this hill! What can I do for him? Is there some Plan B or some way around this?” my question confuses Hans but provides me with my marching orders to get Ben to the finish. As you read these words, imagine a retired Lt Col in the Norwegian army issuing this command in perfect English but with a strong accent—his orders went something like this:

YOU WILL DRIVE TO THE TOP OF THE HILL

YOU WILL PARK THE CAR AT THE FINISH

YOU WILL CHANGE INTO YOUR RUN CLOTHES

YOU WILL RUN DOWN ZOMBIE HILL TO BEN

YOU WILL ESCORT HIM UP THE HILL TO THE FINISH

BEN WILL FINISH

BEN WILL BE A NORSEMAN!

So that’s what I did. I ran 4+ miles downhill to Ben, I found him starting the 3rd switchback, and I accompanied my friend up this damn hill and stayed by his side until the finish.

I went into hiking mode (thank you Coach Liz for making me hike for four hours at the Arboretum during one training session) and keep my heart rate steady in the 130 beat per minute range and powered up these switchbacks at a 20 minute per mile pace. Things turned around in my head during the hike up and I felt better. It was long and sustainable. I could get down my nutrition (one gel and one salt tab every 30 min) and I could look at the mountains and town below getting smaller and smaller. I even texted a picture of the climb to coach Liz! When Jack arrived, he took my picture. My face looked awful. I must have been suffering, but I was okay.

Run course elevation profile

Zombie Hill switchbacks

What was not okay was contemplating the white t-shirt finish. After the checkpoint at the top of Zombie Hill, there is a 4km run to the Gaustablikk hotel. To run the full marathon distance, you must do 10 loops around a course near the hotel. I really wanted to run those loops to get it over with as fast as possible, but my legs just wouldn’t run. I tried to do a pickup and the legs wouldn’t go. If there was a cutoff for finishing, I could surely run, but since I made all the cutoffs, there was no point pushing it without risking injury. We got to the top and then the sun went down, and it got cold. Luckily, at the last refueling stop, we packed gloves, warmer shirts, hats and headlamps. Those carried us another 4k to the hotel where the 600m 10 loop course waited.

The race director and some of the other race staff were at this loop course. The temperature was probably in the mid-40Fs. To add to the superhuman mythos of the Norwegians, they must live in cold weather for their whole lives and are used to not being warm. All the race volunteers watching the course had no propane heaters. They didn’t even have gloves on. They would stand and sit around the lap course without moving and they’re just not cold. In fact, after the race ended and some of the staff came into the restaurant for food, they didn’t seem cold at all. Jack and I were just dying.

Jack and I entered the loop course as directed about one quarter the way into the first loop. We walked with one of the race staff (Bent who manages their Facebook page and does tons of other stuff that makes the race work). He was joyfully carrying Norway’s flag talking everybody up and was very pleasant. This could not last forever. Then I got to the first checkpoint. To track the laps, each athlete receives a card attached to a lanyard. The card has 10 printed circles, numbered one through 10. A race volunteer would punch on of the circles at the end of each lap.

“WHAT DO YOU MEAN THE FIRST LAP DIDN’T COUNT?!” I exclaim while glancing at the punch card in pure disbelief bathed by the light of my fancy headlamp.

As I finished my first lap, I proudly accepted the lanyard and eagerly expected my first punch. He didn’t punch the lanyard. To my great horror, 16 or 17 hours into the race, he said the first lap didn’t count. THE FIRST LAP DIDN’T COUNT!! (It wasn’t a full lap, of course.) After that, I told flag carrying Bent that I knew this was his decision and no longer liked what he did. I told him he was not a nice human being and should walk in despicable shame (he is nice, just not then in my fatigued mind). Further, I told him that not counting the first lap was an infamous deed to be known to history and I would remember it for the rest of my life. Then he laughed. I told him I was serious. We continued to do the loops. I bitched loudly. I ended up forgiving Bent (in my mind, I will not admit it to him directly), but I still can’t let go of this travesty of failed expectation management. (Bent later told me that it wasn’t his idea – he was just the messenger. Thinking about it a month later, he does have my sympathies.)

During the loops we had company from our Norwegian friend and savior Elisabeth (Hans was walking Sami up Zombie Hill so she could make the cut-off). She also introduced us to her daughter, Sophie, whose company raised our spirits. Despite all this support, I couldn’t let go of the first loop, not counting. It was like Herman Melville’s White Whale to me at this point. I’m sure I annoyed everyone around me. When I finally finished, the race staff played the American anthem and took pictures and let me go over the finish line. Done. 18.5 hours. 211th place out of 219 finishers. Jack and I did it. Hardest damn thing.

At that point, we did another three-quarter walk around the loop to get to the restaurant for the post-race buffet. That’s 11 fucking loops. 11.

It ain’t pretty, but we finished!

PART 8 – Afterwards and T-Shirt Ceremony

I was looking forward to eating a huge amount of food after the race. I dreamed I would fill my belly with everything I saw. Large quantities. My gut had other ideas. It was upset about eating sugar all day long. Crackers, Pop Tarts, Gatorade, GU Roctane. It went on strike. All I wanted to do was overeat and go to sleep and my stomach wouldn’t let me. That was almost as bad as the first loop not counting.

Ice cream to the rescue. Ice cream worked. I could keep it down. So, after several cups of ice cream at about 1am, we crawled out of the dining hall to our room and collapsed after a shower (every time I touched my head, I felt all the dried salt other mystery substances covering it from 18 hours of freezing and sweating).

We got up the next day at 9am for breakfast. The t-shirt pick up started at 10am with the awards ceremony at 11am.

I collected my white t-shirt while standing next to all the black t-shirted “cool kids”. Snarky-ness aside, everyone was happy, gracious, limping, and kind. The t-shirts were not your usual cotton/polyester blend; they were very advanced exercise shirts with lots of wicking and fancy stuff integrated into them.

The interesting thing about going up the mountain and getting your black T-shirt is that I had thought (deluding myself) that maybe I had a chance of accomplishing that. When I got to the checkpoint at the top of the run course the day before, I couldn’t then imagine climbing another 3000 feet. I just could not imagine it at all. The level of what they can do compared to what my body is capable of is astounding.

Then all the athletes went outside, stood on the ground and picnic tables outside for the famous group photo. And, yes, it was raining – in the mountains in Norway it seemed like it was always raining. As we all cozied up to each other to fit in the picture frame, a woman next to me made a comment on how this would be the perfect environment for the spread of a little post-race COVID (I tested positive a couple of days after I got home).

Norseman Finishers 2022 (Ben is in the sun glasses in front of the flag pole).

What an amazing story. You are amazing. That you persevered and didn’t quit, when you felt like quitting, yet pushed yourself to what seems like “beyond your limits” and finished that race seems so improbable, yet you did it. Who cares what color T shirt you got….you got one and finished what has to be one of the toughest to complete. It probably doesn’t matter to you, but I am proud of you and happy to tell people that I know you from law school and what you accomplished in Norway! Way to go, Ben.

What an amazing experience. Congratulations!

I read it all, and it sounds absolutely terrible. Congratulations!

Awesome accomplishment!!! Congratulations Ben for getting through it. (Also, very CRAZY!)

Please do not repeat this effort any time soon. Thank you so much for sharing. Encourages me to keep on moving.

There is no amount of money that would get me to try and accomplish what you did accomplish, Ben. Congratulations!

Ben that was Totally AMAZING . Great job . You could have probably slept for a week after that

Isn’t my dad pretty cool

Great read Ben! I sure do hope conditions are better this year, but I’ll be packing for the worst!

This is AMAZING!! What an accomplishment. Congratulations!